In Sarajevo’s old town, local guides find navigating the dense network of old streets a lot easier than charting a path through an even denser tangle of overlapping laws.

While Bosnia’s capital, Sarajevo, was still waking up, a group of tourists from Hong Kong disembarked from their bus near the iconic City Hall.

With no designated parking spot for tour buses in the historic city centre, their driver had to make a stop in a bay normally reserved for intercity transport. It was a routine daily compromise in a city still struggling to adapt to the rhythms of global tourism.

A Bosnian woman in the group in her mid-thirties gave instructions in English to the Chinese guide, before inviting a BIRN journalist to join the tour.

“We’ll cross the river to the left to take a look at the City Hall,” she announced. The guide beside her repeated her words in Cantonese, and the group quickly followed, heading toward the bridge that connects the two banks of the Miljacka River.

It was a small snapshot of the layered economy of translation, labour and cultural mediation that defines a tour guide’s role in Sarajevo – and beyond.

It was also a transaction mandated by laws designed to ensure that destinations are presented accurately – and protect jobs for locals.

In a city like Sarajevo, where the legacies of the Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian empires and former Yugoslavia meet the scars of the wars of the 1990s, the question of which stories are told – and by whom – makes the role of tour guides both practical and political.

“This is one of the few groups that actually hired a local tour guide before coming to the city,” Samra Comor Bekirovic told BIRN, as the group slowly progressed through the city.

Many countries by law require foreign tour groups to hire a local guide. But in Bosnia and Herzegovina’s fragmented system of governance, the enforcement of such rules is inconsistent.

Tour guides have to navigate not just city streets but also a tangle of overlapping jurisdictions, unclear enforcement mechanisms, beside a constant struggle to attract clients in a competitive, poorly regulated, market.

“The law obliges tour operators to hire a local tour guide, but we have no way to fine those who don’t comply,” Comor Bekirovic observed.

“The laws are such that even if someone is issued a ticket, they can just cross the border and never pay it; we don’t have a way to enforce payment,” she added.

Fragmented jurisdiction

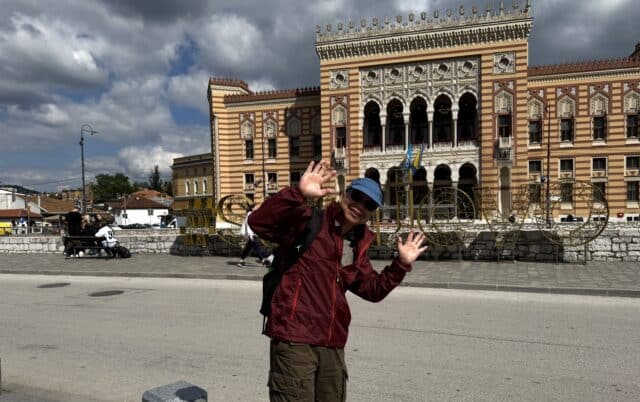

A Chinese guide speaking to a tour group, with Samra Comor Bekirovic in the background. Photo: BIRN.

Tourism in Bosnia is regulated at the levels of cantons, the two country’s entities and Brcko District.

The Serb-led entity, Republika Srpska, and the Bosniak and Croat-dominated Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, both have ministries in charge of issuing tour guide certificates. Brcko District, a semi-autonomous administrative unit, does the same.

To get a certificate, applicants must pass a test of general and historical knowledge. They must be citizens of Bosnia, speak at least one foreign language and have a clean record.

But, in the Federation, they have also to pass tests specific to any one of the ten cantons where they plan to guide tours. They can apply for permits for all ten, if they plan on working in all of them. After receiving a certificate from the Federation, the cantons are in charge of issuing accreditations for guides.

And while all the various laws on tourism say tour guides must be nationals – or foreign citizens with a work permit in Bosnia – none of them strictly oblige foreign tour operators to hire local guides at the destination.

“Since my accreditation says that I work in Sarajevo Canton, I cannot do tours in the [nearby] town of Konjic,” Comor Bekirovic pointed out.

Konjic, where she spent many childhood days, is only 60 kilometres south of Sarajevo. In the past decade-and-a-half, it has become popular among nature and adrenaline lowers.

But Konjic belongs to another canton in the Federation, the Herzegovina-Neretva Canton.

“So, every time I have a group that goes there from Sarajevo, I have to hire a guide from Konjic to take over the tour – otherwise I can be fined,” she explained.

And, unlike foreigners, Comor Bekirovic has to pay fines if she gets them, ranging from 100 to 1,000 Bosnian marks, or 50 to around 500 euros.

The Federation Ministry of Environment and Tourism told BIRN that, although “the law does not specifically say anything in regard to foreign tour guides”, it does regulate who can be a tour guide and under which conditions.

“We have tour guides who apply to get certificates issued by several cantons, and they do this to avoid potential penalties and reduce costs,” the ministry said.

It added that a new draft Law on Tourist Activity is supposed to deal with these matters more clearly in future.

Fewer complications in Republika Srpska

Sarajevo Old Town is known for its huge population of pigeons, which became one of the city’s tourist attractions. Photo: BIRN.

Thanks to its simpler, unitary administrative structure, tour guides in Republika Srpska have to pass only one test and get one certificate.

“After they pass the test, they can work on the whole territory of the entity,” Marko Radic, director of the Tourist Organisation of Republika Srpska, told BIRN.

As in the Federation, the law in Republika Srpska prescribes who can be a guide and under which conditions.

“After they receive the certificate, they can either be self-employed, or employed by a tourist agency,” Radic noted.

Similarly, Republika Srpska-entity law obliges foreign tour operators to hire local guides when visiting the entity. But, as in the Federation, implementation of the law is weak.

“I can’t remember a case where a foreigner was fined for guiding tours in Republika Srpska,” Radic told BIRN, adding that the “treatment of locals in this case is unjust.

“The purpose of tourism is to bring jobs to locals – but those locals are the only ones paying the fines in the end.”

High costs of running businesses

Samra Comor Bekirovic. Photo courtesy of Samra Comor Bekirovic.

While Bosnia is becoming more popular as a destination, with almost three million registered overnight stays in 2024, tourism still officially brings in only 2-4 per cent of the country’s GDP and tends to be overlooked by governments.

But, in the absence of exact measurements of tourism at national level, which would include other forms of spending – on gas stations, restaurants, mechanics, hairdressers, dentists, for example – tourism’s total contribution to the economy is likely to be higher than the official figures suggest.

The director of the Tourist Organisation of Sarajevo Canton, Haris Fazlagic, sees tourism as “a key branch”, noting that Sarajevo airport aims to handle 2 million passengers in 2025.

“Sarajevo has become an entry point for many tourists, and the government has recognised that within its new tourism development strategy up until 2030,” Fazlagic told BIRN.

According to Fazlagic, the new strategy includes increased control measures during the peak summer season, to reduce the number of illegal tour guides and, in coordination with the police, to reduce the number of pickpocketing incidents.

“We are in daily communication with tour guides, and we have tried to send appeals [for rule changes] to the most relevant ministries,” he added.

“Tour guides are crucial partners in the development of tourism in the canton – but some things are in the hands of other ministries.”

While hoping for change in future, and fighting for every client, Comor Bekirovic meanwhile has to manage the high costs of running a tour business in an entity with some of the highest tax rates in Europe.

“Since I mostly work with foreign agencies, due to legal obligations, I had to register my tourist agency as a company,” she noted.

But the bureaucratic red tape does not stop there. “To get a tour guide certificate, I must be registered at municipal level as self-employed, or as an independent worker, which means I must have another fiscal device for that,” she added.

To run her business, she and her sister, another tour guide for the same company, have had to buy three fiscal cash registers.

“All of these legal requirements bring in extra costs – for administration, audits, rent and taxes,” she said. “In the end, I have to make at least 30,000 euros annually to make this sustainable.”