North Macedonia’s government is reaching out to the some of the biggest names in crypto but has still to write the rules for a field that already boasts thousands of ‘players’.

As a teenager in the late 2000s, Darko was a gamer, good enough at the multiplayer online battle game DotA to compete for prizes paid in bitcoin.

“I was an 18-year-old kid; I didn’t take it seriously,” Darko, now 35, told BIRN. “Every month I’d get 10 or 20 bitcoins and use them to buy other video games.”

He recalled those days when he opened his own dental clinic in 2016, and one of his employees said she planned to begin ‘mining’ bitcoin.

His curiosity piqued, Darko went online to see what was happening in the world of cryptocurrency, digital assets that emerged as alternative payment methods following the 2008 financial crisis, when many people lost faith in the traditional banking system.

He was shocked to find that the value of a single bitcoin had soared to over $20,000, a far cry from his DotA days when the currency was in its infancy.

From its launch in 2009 to the latter part of 2013, bitcoin’s value fluctuated below $10, peaking only once at $26. Since then, it has skyrocketed. Darko wanted a piece of the action.

Darko is not his real name. Like other crypto enthusiasts interviewed by BIRN, he insisted on anonymity.

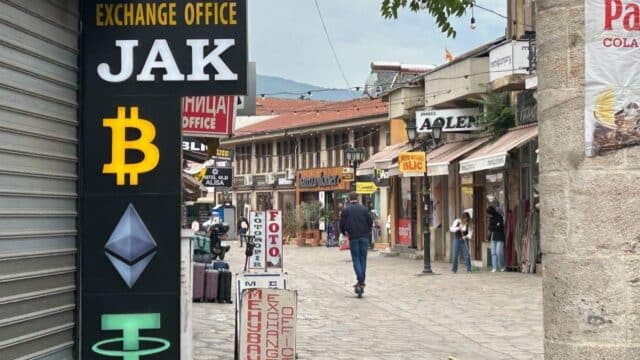

Cryptocurrencies might be increasingly visible, but the field remains a grey area, often associated in people’s minds with pyramid schemes, fraud, or crime.

In North Macedonia, where Darko lives, cryptocurrencies are not regulated, which means that those who have invested have no clear way of integrating these assets into the formal financial system.

Some fear that speaking publicly about the topic might attract unwanted attention from the authorities.

Since taking office in 2024, right-wing Prime Minister Hristijan Mickoski has promised to regulate the crypto market, arguing it would bring more money into the country and state coffers.

When Mickoski visited Washington during Donald Trump’s inauguration as president in January, Chris Pavlovski, a Canadian businessman of Macedonian origin and owner of the social network Rumble, introduced those travelling with the prime minister to representatives of Tether, one of the world’s largest crypto companies.

Then in May, Mickoski hosted Pavlovski and the owner and CEO of Tether, Giancarlo Devasini and Paolo Ardoino.

The talk was of turning North Macedonia into a crypto hub, a new El Salvador, which in 2021 became the first country in the world to recognise bitcoin as part of its economic system and require all economic actors to accept it as payment.

Under pressure from the International Monetary Fund, El Salvador watered down the policy, and companies are no longer required to accept bitcoin payments if they do not wish to. But the small Central American country remains synonymous with cryptocurrency.

“I love small countries because they adapt faster,” Ardoino, Tether’s CEO, said during his visit to Skopje.

Unregulated market

Chris Pavlovski (left), a Canadian businessman of Macedonian origin and owner of the social network Rumble, connected North Macedonia’s government officials with Tether, one of the world’s largest crypto companies. Photo: BIRN

On the one hand, lack of regulation and oversight opens a door to illegal transactions, money laundering and terrorism financing.

On the other, those who have simply invested in the crypto market can face a raft of problems, from improper taxation to banks rejecting their funds.

Goran, from Skopje, said he has never “cashed in” his earnings from seven years of investing in crypto because of the lack of regulation.

He was one of almost 90 individuals who submitted responses to a BIRN survey. While the others who are quoted in this article insisted on anonymity and have been given pseudonyms, Goran agreed for his real first name to be used.

Goran said he feared that integrating cryptocurrencies into the formal system might get him into trouble.

“Maybe criminals know how to justify these funds, but I don’t,” he said.

Atanas, however, said he has transferred crypto earnings to a bank account, declaring it as “internet earnings” and paying personal income tax on it. He co-owns a crypto company registered outside the country.

“We’re trying to be clean with taxes on our own initiative, but the chances are that no one will notice because it’s unregulated,” he told BIRN.

Atanas receives his salary in cryptocurrency and often withdraws cash from crypto exchanges.

“Realistically, regulation wouldn’t even help because when an industry is unregulated, that’s when the biggest opportunities for earnings exist,” he said.

Crypto enthusiasts we spoke to argue that most people in North Macedonia, even if they’ve heard of cryptocurrencies, are not financially literate enough to grasp the complexities of the field.

Many view crypto either as a scam or as a means to make a fast buck, rather than a field requiring technical and financial knowledge.

Even Darko, who is now one of the more active people in North Macedonia’s crypto community, not only did not believe these currencies would gain such value but also made a major mistake when he first started using crypto.

“I still have bitcoins, and I have the old laptop I used to play video games,” he said. “But I can’t access them, and no one can help me now; I probably have five or six bitcoins on it.”

Mostly young men

Nikola Levkov, an economics professor at Cyril and Methodius University in Skopje. Photo: BIRN

Binance, one of the world’s largest crypto exchanges, says it registered a 40 per cent increase in users in 2024.

It counts some 200,000 citizens of North Macedonia among its account holders, or roughly 11 per cent of the population.

It is hard to say whether all of these are ‘authentic’ crypto users.

The respondents to BIRN’s survey have, on average, been involved in crypto for about three and a half years; Binance is their most popular exchange, and, besides bitcoin, they also trade in Ethereum, Solana, Tether, and Ripple.

Most said they have made a profit, but a few admitted they were in the red.

According to a 2022 study co-authored by Nikola Levkov, a professor at the Faculty of Economics at Cyril and Methodius University in Skopje, over 80 per cent of crypto users in North Macedonia are male, most of them between the ages of 19 and 34, usually living in urban areas having completed higher education.

The profile is similar in other countries.

Generally, users are aware that investing in crypto is riskier than investing in stocks, and while some are IT enthusiasts, most are motivated by the prospect of getting rich, quick.

“It’s significant that two-thirds are passive investors who buy cryptocurrencies, don’t engage further in trading, but wait for their value to increase and perhaps sell when the value rises significantly,” Levkov told BIRN.

This was exactly the case for one of the survey respondents, who wrote: “Although I’m currently at an unrealised loss, I believe in the future of cryptocurrencies and I believe that in 5-10 years from now, I will have much higher profits.”

According to Levkov, bitcoin has no “intrinsic value” like, say, gold.

“Rather, it is a financial-technological innovation, mainly driven by people’s belief in the value of that currency, and they invest in it expecting its value to continue rising.”

Today, one bitcoin is worth over $100,000. If Darko had access to his old crypto wallet, he’d be half a million dollars richer.

“But what can you do?” he shrugged.