“I’m not retired because they won’t let me go. I was ‘forced’ to become an executive manager in 2020,” says Dragutin Varga, CEO of ITAS Prvomajska (ITAS First of May) from Ivanec, in the north of Croatia.

“It was never a priority for me. Nor is it appropriate for a union man to be a CEO. But all the managers so far have been thieves, and we wanted the company to survive, so the Board of Directors asked me to do it,” he adds.

This year marks 20 years since Varga’s union launched a struggle to take over the only machine-tool factory in Croatia.

The production of CNC (Computer Numerical Control) machine tools is considered the apex of the industry, as it involves making machines that produce other machines.

The struggle included hunger strikes, court battles, acts of civil disobedience and every other form of resistance the workers had at their disposal.

Ultimately, it led to the factory being returned to the workers after years of legal and grassroots efforts.

Varga, who led the union during that time, told BIRN that he was prepared for anything except physical violence.

“I kept telling people not to get into physical fights, that was our basic rule,” he says.

He is probably the only trade unionist in Croatia today to be a factory director.

But, as he points out, his task is not to manage workers in the traditional sense but to represent their interests.

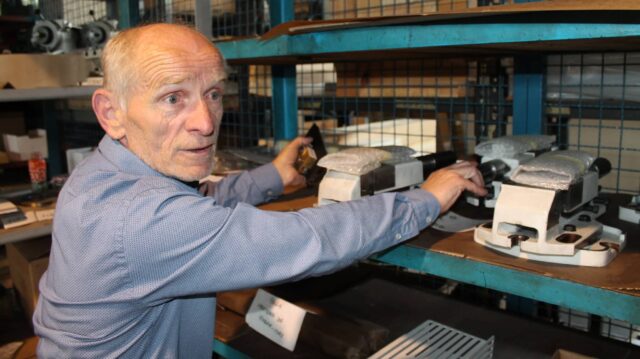

A machine worker by trade, Varga has worked at ITAS since 1978. Now 67, he should be retired. A short man with a commanding presence, piercing blue eyes, direct speech and charisma, a cigarette is always in his hand.

ITAS was founded in 1960 and steadily developed until 1990. Following the 1974 changes to the Yugoslav Constitution, “self-management” became the guiding model for all companies, including ITAS.

Workers’ self-management refers to the unique economic and political system developed in the former Yugoslavia under Josip Tito after World War II.

Designed as a Socialist alternative to the centralized economies of the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc, it aimed to give workers direct control over production within a Socialist state structure.

While the system had flaws, it was more effective than the Soviet-style planned economies, which was one reason why the former Yugoslavia enjoyed higher living standards than Eastern Bloc countries.

Privatized ‘in a thieving manner’

One of the protest actions by ITAS workers on the streets of Ivanec. Photo: ITAS Archives.

With the change of political system and the transition to capitalism in 1990, the privatization of socially owned property began.

“ITAS was privatized in a thieving manner. The value of the factory dropped multiple times. They had already cheated the workers, who were supposed to decide on the offer of shares to retirees as well,” Varga recalls of the 1990s. “That’s where the first robbery happened.”

From 1991 to 1995, as Croatia fought its war for independence, while part of the population was on the front lines, the country’s wealth was silently transferred from social to private hands.

Much of this occurred beyond the bounds of legality, away from the public gaze, which was focused on the war.

ITAS workers wanted to buy back shares in their company but were unable to obtain a majority stake. They had to pay for their shares in instalments deducted from their pay.

“The company took 19 instalments from our salaries – but never transferred that money to the Privatization Fund. I wanted to sue the director because we didn’t know where our money had gone,” Varga recalls.

As a result, the workers were left without a majority stake. Thirty-two per cent of the company remained in the Privatization Fund. Meanwhile, various privatisation-investment funds, PIFs, began buying shares. One of them, PIF Sunce, acquired 29 per cent.

“When you add that up, it reaches 61 per cent – which is how the workers lost their seats on the Supervisory Board,” Varga explains.

Serious problems emerged in the late 1990s.

“Salary delays started. We asked the County Prefect at the time, Marijan Mlinaric, to help us. On December 30, 1999, money for our salaries was deposited into the ITAS account – but by January 3, 2000, it had disappeared – and the workers still hadn’t been paid.”

As a union representative, Varga confronted the director to ask where the money had gone. He also demanded that the Supervisory Board be convened and the director be removed.

The director resigned, but under favourable conditions, receiving six months of extra salary and a severance package. Varga was fired.

“I got fired because I was bothering them,” recalls Varga.

He was reinstated to his job after two years by a court ruling, however; union representatives enjoy immunity from dismissal so that they can represent workers freely.

During those two years, the management planned to follow the same model of privatization that was often repeated in Croatia: push the firm into bankruptcy and then sell off the real estate.

The factory was bought by the Breza company, owned by the late Marija Brezovec, Mayor of Ivanec from 2001 to 2005, and her son, Bojan. At the time, people holding political office often took part in privatizations.

“After the court returned me to ITAS on July 13, 2002, I continued to work at my job until 2003, when I saw that we were working more and more and there was no pay,” Varga recalls.

They were not even able to get the legally guaranteed minimum wage and the management refused to negotiate a collective agreement with the workers.

The workers went on strike in September 2003. That month, the Brezovec family founded another company, ITAS Nova, which bought the property, real estate and machinery of ITAS.

The new owners brought in a security company to prevent the workers from entering the new factory, but they broke through the fence anyway and occupied it and founded a Strike Committee that took over the company.

Wall built though the factory floor

Gabrijel Valentino (20) has been working at ITAS since he was 17. Photo: Vuk Tesija/BIRN.

Paradoxically, ITAS no longer owned its own machines and hads to pay the new firm rent.

“ITAS had to pay ITAS Nova a monthly rent, and on that basis, they were extracting 200,000 kuna (some 30,000 euros) from ITAS every month,” Varga recalls. He saw it as a deliberate attempt to destroy the old company.

“In the meantime, they started selling off the land. They even built a wall through the middle of the factory. We couldn’t move from one part of the plant to another. In 2005, they began demolishing the factory. We weren’t getting paid. We saw where it was going,” Varga says.

The next day, he got on a forklift and tore the dividing wall down. The workers dismantled it completely in just 20 minutes.

The police were called but workers surrounded them and prevented Varga from being taken away.

“I had 200 people behind me, and there was no way I was going to give up then,” Varga recalls of those critical moments.

“Even though the real estate was registered under the new owner’s company, we didn’t back down. It had been stolen, and legal proceedings would follow. The workers stood guard around the clock. We never left the factory,” he says.

The occupation of the factory lasted from 2005 until February 2006.

Eventually, bankruptcy was declared, and a court-appointed bankruptcy trustee was tasked with liquidating the assets and paying off creditors.

“The bankruptcy trustee refused to [let us] take on new jobs, because if the factory worked, we might survive. He thought that’s how he would get rid of us,” Varga says.

This was the turning point, when Varga began planning to return the factory to the workers.

At the bankruptcy hearing, when creditors were invited to register their claims, it was established that ITAS workers held 52.8 per cent of the claims.

Back in 2004, 165 workers had sued the then-owners, Marija and Bojan Brezovec, for unpaid salaries dating back to 2000. The court ruled in favour of the workers, ordering the company to pay more than 4 million kuna (over 500,000 euros) in back wages.

That had made the workers the firm’s largest creditors, effectively giving them majority control over ITAS.

“At that moment, we had no electricity. It had been cut off due to unpaid bills. That’s when we went on a hunger strike,” Varga remembers.

They were left with no electricity, no contracts, and a bankruptcy trustee intent on shutting the company down.

Varga and 17 workers went on a hunger strike, demanding that electricity be restored. Pressure mounted at the local and regional level, with politicians lobbying the then-Prime Minister, Ivo Sanader. Sanader eventually advised the national electricity company to restore power to ITAS.

‘They called us Yugonostalgics’

On the wall of the factory hall is a large mural that reads: “Give the factories to the workers”. Photo: V.Tesija/BIRN

After three days, electricity was restored and production resumed.

With the workers now holding a majority stake, they replaced the bankruptcy administrator and appointed Ivan Polan, who helped get the company back on its feet.

Operations resumed, and on January 1, 2007, the workers officially founded the company ITAS Prvomajska. This marked the beginning of better days.

Over time, the factory paid off its debts and resumed full-scale production. Business partners returned.

“They called us Yugonostalgics, but this is better than it was in Yugoslavia. In Yugoslavia, the workers couldn’t dismiss the CEO – but at ITAS, they can,” says Varga. He adds that ITAS Prvomajska has invested more than 5 million euros in development and new machinery to date.

Even after resolving the ownership issue, ITAS struggled with various executive directors who were brought in.

The final straw came at the end of 2019, when the director was fired after workers once again went unpaid for two months.

They then appointed Varga head of the company. He inherited two months of unpaid wages and had to face the COVID-19 pandemic.

Nevertheless, he managed to stabilize the business. Today, ITAS Prvomajska works with some of the largest companies in Croatia and exports most of its products to Germany. Its German partners include Kunzmann, Efco, Adams, and Mag-Eubama.

“If I had known it would be so easy to be a CEO, I would’ve done it sooner,” he jokes.

“Today, I have a ‘kindergarten’ – 30 students training for the professions we need. Workforce is not a problem,” Varga says confidently.

ITAS today employs 120 workers and eight engineers. As Varga walks through the plant, workers stop him to say hello. He greets everyone and frequently returns to the production line himself when problems arise.

The atmosphere on the factory floor is productive but relaxed. Music plays in the background and the workers are in good spirits.

“It’s good here because we’ve done well. The team is great, lots of young guys, and the older workers support and help us,” says Gabrijel Valentino, aged 20. He joined ITAS at 17, straight out of school.

“I don’t like weapons but we also have the capacity for military production. That’s what everyone’s looking for now – and we have experience from the war,” Varga says, hinting at future plans.

On the wall of the factory hall is a large mural that reads: “Factories to Workers”, along with the dates of the strike, the hunger strike and the founding of ITAS Prvomajska.

It’s a tribute to the perseverance and struggle of the workers who saved their factory, not by giving in to political or corporate pressure, but by refusing to surrender.

Today, the factory is truly theirs.