We won’t claim to be totally ignorant to the Ducati brand, so the arrival of the Italian marque into the motocross world comes with a surface level of familiarity. But if you’re anything like us, your head is so far in the dirt that words like Panigale, Superleggera, and Desmosedici aren’t in your immediate vocabulary. In an effort to better understand the all-new Desmo450, and the signature desmodromic valve system that is at the heart of every Ducati, we sat down with Davide Perni, Technical Director Off-Road at Ducati. Davide is charged with bringing the MotoGP-dominating brand off the tarmac and into the dirt, a task that introduces new technology to the motocross world, and brings a whole new challenge to a brand famous for high revs, and breakneck horsepower.

Breaking It Down

“Unfortunately for us, we don’t often explain how the desmo system works, because it’s quite obvious for us,” admitted Perni. The desmodromic valve system has been elemental to Ducati for close to 75 years now, and is a well understood concept in the road racing world. Ducati engineers literally can’t recall the last time they were asked to explain it to anyone. Fortunately, Perni was patient enough to break it down in simple terms for the noobs in the knobby world.

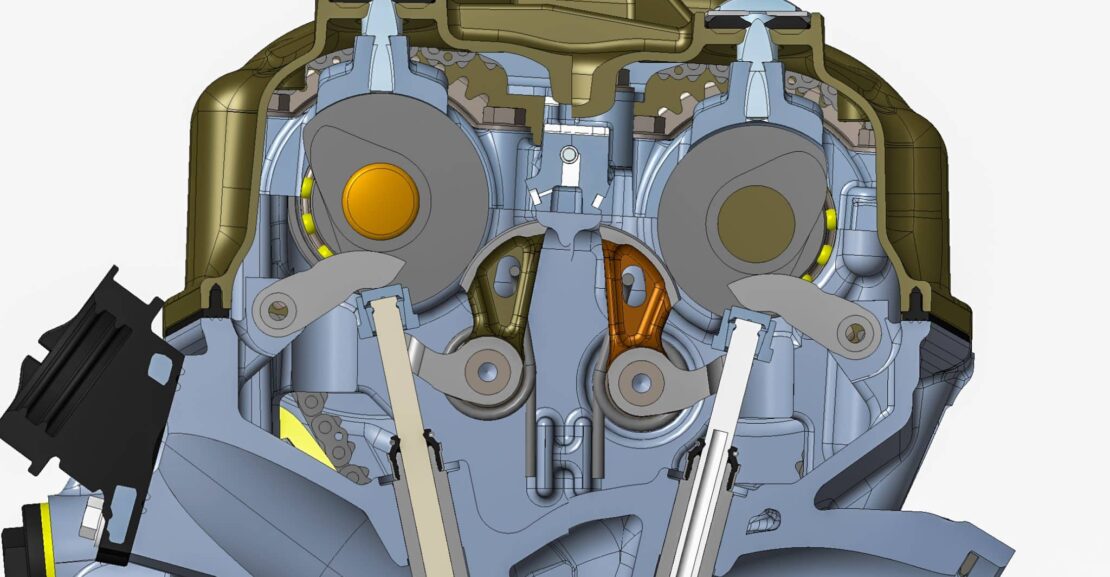

“In a normal valve engine, the cam works directly with the valve to open it, and to close the valve, normally we have a spring,” said Davide. “With the desmo system, you see that we have two profiles on the camshaft for each valve—you have one rocker arm for the opening and one rocker for the closing phase.”

With the valves being both opened and closed mechanically, rather than using a spring, this means the poppet valves are under positive control at all times. The word “desmodromic” actually comes from two Greek words, “desmo” meaning controlled or linked, and “dromic” meaning a track or racecourse. Having this much control over the valve opening and closing has three distinct advantages, according to Davide.

“First, the acceleration of the opening of the valve is very high—more than the normal system. You can also have high acceleration for a normal system, but only for the opening phase. Not for the closing phase because you have a spring, and the spring is designed to have a proper force based on mass of the valve multiplied for the maximum acceleration that you want.

“The desmodromic system allows us to have more time where the valve is completely open, also in the lower rev. This allows us to increase the quantity of oxygen and fuel that enter the cylinder. The opening phase of the valve is still bigger than [that of a] normal system. You can have a very big acceleration also for the slower rev.”

“The second advantage is that you have reduced friction on the system,” Davide continued. Since the camshafts don’t have to press against the valve springs during the opening phase, this is less energy spent by the engine. The lack of frictional loss is most significant in the low-to-mid range.

“The last advantage of this system, and this is our technological flag, is that you can achieve a very high rpm limiter with this system. You don’t have the limiter related to a coil spring.” Davide can lay out the precise engineering terms for you, but in plain language, you can rev it to the moon and it won’t float the valves.

“When you need to achieve a very high rpm, consider that our Panigale V4 production engine, the limiter is fixed at 16,500 rpm. That’s a standard homologated street-legal engine. But the normal timing system cannot allow this kind of rpm.”

There is a lot of pride and heritage behind the desmodromic system, but that doesn’t mean Ducati is ignorant to the drawbacks, as Davide went on to describe. “The system is a bit complicated, and requires a lot of quality and accuracy in the manufacturing of the camshaft profile and the rockers. The weight of the completed system is a bit more than a normal system because you have two rockers, and the camshaft is a bit heavier than a normal camshaft.”

Despite the weight, Ducati engineers maintain that the Desmo450 engine is the lightest DOHC 450cc engine in its class. “[Compared to] the competitors with two camshafts, the Kawasaki, Yamaha, Suzuki, our engine is still the lightest. The weight is only 26.5 kilograms (58.42 pounds).

“The other bad point of this system is the cost,” Davide said. “The accuracy and the machinery that these camshafts require are very expensive. The cams and crankshafts are made directly inside our factory, and we manage by ourselves. Because I repeat, these are not easy components from a manufacturing point of view.”

According to Perni, this also means we shouldn’t expect to see any third-party cams or cranks for Ducati dirt bikes.

A Brief Desmo History

The technology actually dates back to the 1950’s when the desmodromic valve system was adopted by (not invented by) Ducati. At the time, valve control technology was a major mechanical challenge, so renowned Ducati engineer Fabio Taglioni applied for the patent and built the desmo system into the company’s 125cc race bike. Ducati’s 125 GP Desmo ran away with the 1960 Grand Prix victory, and the desmodromic valve system has been fully embraced by the Bologna brand ever since.

Thanks to modern materials, valve control is far less of an issue today, making the desmodromic system less of an advantage than it once was. But in the formative decades of Ducati racing development, the desmo system defined the soul of the company, and 65 years later, it sees no reason to alter course. It’s the system they know best, and there is a lot of pride and heritage behind the design.

Putting Power In The Dirt

In terms of motocross, the horsepower race is over. At a certain point, big horsepower becomes more of a burden than an advantage, and we found that limit pretty quickly with the early generation 450 motocross bikes. This was apparently difficult for Ducati engineers to hear. Coming from the tarmac, where Ducati can deliver enough power to send you into a time warp, and enough ride-control technology to somehow keep you attached to the ground and moving in your intended direction, the idea of curbing power down for a more manageable delivery didn’t quite compute.

Davide recalls back to the early days of Ducati’s motocross development. “We fight a lot in the beginning,” he said with a laugh. “Our 1000cc displacement bike is around 237 horsepower. For engineers, this means if you have around 230 horsepower per liter, this means a 450, more or less, you have a reasonable 100 horsepower, easy. But [our test riders] say, ‘Guys, please stop!’ Based on motocross, when power increases over 65 to 68 horsepower, a rider cannot ride well anymore. So, the target is not the maximum power because we’d risk creating an engine that nobody can use. For the 250, we will see. But for the 450, this is not the case.”

Learning to limit the power rather than unleash it actually came during the Desert X development, which was an important step in Ducati’s understanding of riding in the dirt. Five-time World Enduro champion Antoine Meo was central to the Desert X development, Ducati’s adventure model that was introduced in 2022. Their first stab at a dedicated off-road bike was admirable, and the subsequent Desert X Rally (2024) was even more impressive. The most direct way to begin motocross testing was to take the 937cc twin-cylinder Desert X on the motocross track.

“It was quite crazy. When you see a 180-kilogram (400-pound) two-cylinder jump on a motocross track, people with the other motocross bikes were scared!” Perni said with a laugh. “But, that was really good to understand the potential of the system. It was a good experience for Antoine because when he understood the potential of the traction control, it pushed us to improve the system for off-road.”

As we also know, nine-time FIM Motocross World Champion Antonio Cairoli along with Italian MX hero Alessandro Lupino are behind the Desmo450 development. Perni himself also comes from a motocross background, having worked as an engineer and race team manager for Husqvarna. The right people are on the job, but there was still a lot of push-pull in building Ducati’s understanding of the dirt. Fortunately engineers listened to the experts and came to terms with the blasphemous notion—more power isn’t always better in the dirt. They settled on a peak horsepower of 63.5 at 9400 rpm, and a rev limiter of 11,900. Modest numbers according to Ducati’s engineering math, yet still a benchmark for the class.

Getting Plugged In

Almost as directly in Ducati’s wheelhouse as the desmo valve system is ride control technology. While their expertise once again lies on the pavement side, adapting the electronics to the dirt was a vital aspect of the Desmo450’s design. Perni talked about the all-new Ducati Traction Control, or DTC.

“We are experts on the electronics that apply to two wheels,” said Perni. “Ducati was the first manufacturer that put traction control on the production bike; it was 2007. Traction control is not completely new for off-road, but let me say that DTC is very different with respect to what is in the market now.”

“The real advantage of our system is the traction is not like a map that cuts the power. We have an algorithm that is under patent pending, that can manage the answer of the system based on the acceleration and the position of the bike in space.”

Rather than relying on wheel speed, DTC utilizes an onboard sensor to feed information to the electronics. “We use a sensor that is state of the art called BBS—Black Box System. Inside you have an accelerometer and gyroscope sensor. We’ve had this science for 20 years, so it is quite common technology. The challenge is using this technology without the speed of the wheels.”

Ducati opted to go without wheel sensors not only because it felt there was a better way, but because FIM regulations do not allow it for competition use. Yes, Ducati expects that even the pros will want to use DTS. Keep in mind, they come from the road racing world, where the top teams in everything from MotoGP to World Superbike utilize a full suite of electronic rider aids.

“The rear wheel speed, you can measure in some way, but the problem is that normally in off-road you still work with 30-, 35-, 38-percent wheel slip,” said Perni. “Consider that in the road race when you are more than 3-percent slip, the engineers go crazy because it’s too much. [laughs] Here we are completely in another world.

“This group of electronic engineers develop a new software system, an algorithm we call Job Detection Function. The system recognizes when the bike is in the air and when it is working on the ground. Because when you are in air, you need the throttle to modify the balance of the bike, and in this moment, the system cannot cut the power. Job Detection Function is under patent because is a very important function on the system.”

Launch control, engine brake control, two riding modes and a built-in quickshifter are also part of the electronics we can expect to find on the Desmo450. For the DIY crowd, don’t worry. “Obviously you have the possibility to disengage the system,” Perni added. “You want to switch off every control, you can do it, absolutely.”

And?

So how does it all work? Do the claims add up? We haven’t gotten our dirty hands on a Desmo450 yet. At this point our goal is to learn more about what’s under the hood and what exactly makes this bike unique. Now that we have a better understanding the Ducati-ness of this all-new player, we’re ready to put the desmodromic power and Ducati electronics to the test. Watch the pages of Dirt Bike Magazine for the full review of the 2026 Ducati Desmo450 motocross bike coming soon.